By Mary Lipsey and Debi DeLoose. In the late 1800’s an iron truss bridge was…

Fairfax County Irish Residents

The early population of Fairfax County, Virginia was composed primarily of Northern Europeans, many of whom were holders of land grants or individuals designated to act as caretakers of land grants for their proper owners living in England. Over time, English paupers migrated to this country and served as laborers or overseers for the large landowners. Later, these laborers acquired small parcels of land and became yeoman farmers. Their primary crop was tobacco, supplemented by small grains, such as wheat, oats, and Indian corn.

While Irish and Scottish individuals came to this country as early as the 1600s and 1700s, the greatest influx of Irish emigrants voyaged to America in the mid-19th century, during or following the Great Potato Famine of 1846-1847. Famines had occurred over a number of decades, but never as geographically widespread as the 1846-1847 famine. One day the potato fields were a deep green color and the next day the fields were a black putrefying mess of rotting potatoes. With little to no food, there was little means of earning an income and putting food on the table. Amongst an exploding population, half of the Isle of Erin’s population of 8,000,000 souls boarded wooden 3-masted schooners, rode in the base of the ship in the dark, damp and dank steerage to America. Some traveled to England, Canada, South Africa, or Australia, but a large portion of the emigrants voyaged to the United States. They arrived at ports of Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, or New Orleans, but the greatest numbers came to the port of New York. From these ports, the emigrants traveled in a north, south, and west direction. A large percentage of Irish came to New York City and never left. A significant number continued to travel west to Ohio, Illinois, and other points west to acquire employment. Most Irish were uneducated and illiterate, and quickly settled for jobs as uneducated agricultural laborers. Others worked on the infrastructure jobs, such as the canals of the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) and the Erie canal and the railroads.

Many of the Irish that settled in the Fairfax County area arrived at the port of Baltimore and traveled south, primarily on foot, looking for work. Unskilled labor was hard to acquire; slaves filled most of those requires in the 1850s. This was to change in the 1860s with the outlawing of slavery through the 13th amendment and the Emancipation Proclamation.

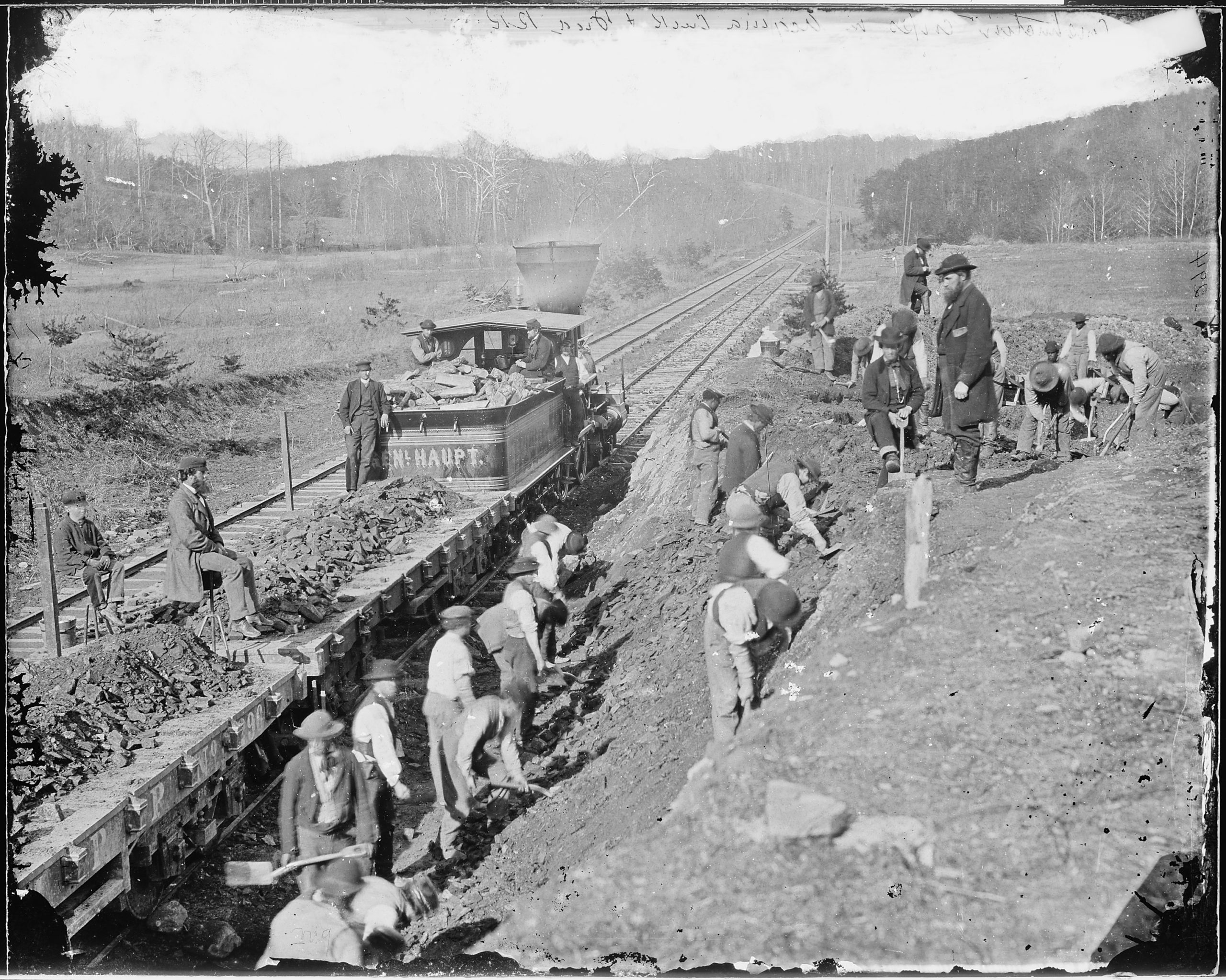

In the early 1850s, the railroad came to Fairfax, in the form of the Orange and Alexandria (O&A) Railroad, the Alexandria, Loudoun, and Hampshire (AL&H) Railroad, and the Manassas Gap Railroad. The AL&H Railroad traveled through Fairfax County through Vienna. The O&A Railroad traveled through Fairfax through Pohick Valley and Burke’s Station.

Many of the male Irish emigrants went to work building and repairing the railroad. Back-breaking work, they would cut the railroad cut, then build the rail bed, cut and lay railroad ties, and finally lay the iron or steel rails, nailing them into place.

The Irish settled in various places in Fairfax County. Jane Allison, an unmarried elder emigrant, farmed in Fairfax. The Carroll family came to Fairfax County and settled in Fairfax Station, and were ultimately buried at St. Mary’s Catholic Church, Fairfax Station. Thomas Carroll won premiums at the Alexandria and Fairfax Agricultural and Industrial Fair for the best milch cow, best 2-year old bull, and best cabbage, beets, radishes, parsley, and salsify. Jeremiah Casey, a native of Ireland, applied for citizenship in 1852 and voted in favor of secession from the Union in 1861. Timothy Cashmen traveled from Ireland to Fairfax and raised horses and hogs on a small farm.

In 1838, the Hamills and the Cunningham’s donated a tract of land to the Diocese of Richmond in hope of having a church built and a Catholic cemetery consecrated. A cemetery was immediately created, but it was sometime before the church was built. When drafted to build the nearby O&A Railroad, the Irish laborers, being Roman Catholic, soon asked for a church to be built for worship. Previously, the laborers had been worshiping on and in front of railroad cars. They built a small clapboard-sided white country church with a steeple. Inside were two rows of wooden pews, leaded up to a pulpit.

In September 1862, following the Battle of 2nd Manassas, the church yard was used to place wounded Union soldiers, where Clara Barton and others cared for them, prior to placing them on the railroad and carrying them to Alexandria and Washington City for medical attention. The church pews were taken from the church by soldiers and used for campfires, only to be replaced later in the war by President Lincoln. This church, now called St. Mary of Sorrows Catholic Church, still stands off of Ox Road in Fairfax Station.