By Mary Lipsey and Debi DeLoose. In the late 1800’s an iron truss bridge was…

Burke in the War of 1812 – The Coffer Brothers Dash to D.C.

Burke was rural and sparsely populated in the early 19th century. The 1810 Federal Census counted only 13,111 people in the entirety of Fairfax County. “Burke” was part of the Providence District; the “Burke” name was still decades away. The Coffer family settled in Burke through a 378 acre land grant to Francis Coffer in 1728. Much of this land is now in Burke Centre’s Woods and Ponds neighborhoods. Thomas Coffer (born 1773, died abt. 1862) and his brother Francis Coffer (born 1784, died abt. 1863), were the great-grandsons of Francis Coffer. These Coffer brothers were born too late for the American Revolution, but served their country in the less remembered War of 1812.

In August 1814, Thomas Coffer was undoubtedly a busy man with a wife (Ann Simpson Coffer), six children (three boys and three girls), and nine slaves. He was a Captain in Colonel George Minor’s 60th Regiment of the Virginia Militia. His unmarried brother, Francis Coffer age 27, served as an Ensign in the 60th Virginia which consisted of 600 men and 100 cavalry organized into 17 companies. The 60th was part of the 10th Military District, commanded by Brigadier General William Winder.

On August 18, 1814, British warships landed troops at Benedict, Maryland. Colonel James Monroe, the U.S. Secretary of State (and later 5th President of the United States), was sent with General Winder to watch the British. On August 22nd, Colonel Monroe sent a dispatch to President James Madison advising him that American troops were marching out to meet the British invaders. Colonel Monroe advised the President to blow up the bridges leading into Washington, D.C., and to arrange for government records and valuables to be sent out of the city. This message panicked the Washington, D.C. civilian population (which numbered about 8,000) with most fleeing to the countryside. But the Secretary of War, John Armstrong, refused to believe that the British would advance to Washington, D.C, he thought they would target Baltimore or Annapolis. The Secretary told the Chief of the Washington, D.C. Militia, “they (the British) would not come with such a fleet without meaning to strike somewhere. But they certainly will not come here! What the devil will they do here? No! Baltimore is the place, Sir.”

Others in D.C. took Colonel Monroe’s warning seriously and on August 23, 1814, Colonel Minor received orders from President Madison to muster and march the 60th Virginia to the capital. The muster was so hasty that many of the men showed up without guns. The Virginia men marched to Washington, D.C., entering the nearly deserted city around sunset. The 60th proceeded to the U.S. Capitol where Colonel Minor went in search of guns and other supplies, leaving his Captains in charge.

Colonel Minor contacted a local friend, who took him to President James Madison. The President referred Colonel Minor to Secretary of War Armstrong who, still dismissing any real danger to the city, advised him that the Army Quartermaster, Colonel Henry Carberry, would supply his regiment in the morning. Colonel Minor, frustrated at the orders to muster quickly, then the abrupt dismissal, returned to the Capitol and spent the night with his Captains and men in the House of Representatives chamber.

In the meantime on August 23rd the British, surprised by the ease at which they were infiltrating the countryside, debated whether or not to march on Washington, D.C. Some British officers, emboldened by their taking of towns and supplies, wanted to push on. Others feared that the Americans were gathering for an attack. British commanders Rear Admiral George Cockburn, and Major General Robert Ross decided to risk an assault on the capital city, and had their men marching towards Washington, D.C. at 5 AM on the morning of August 24, 1814.

The morning of August 24th Colonel Minor, again leaving his Captains and men, sought out Colonel Carberry. Minor was unable to find Carberry, but did find General Winder who authorized the 60th to draw supplies from the armory. It was late morning by the time the 60th got to the Armory. The armory clerk was another challenge. The clerk, perhaps not understanding the danger to the city, or maybe just enjoying his bureaucratic power, insisted on personally, and meticulously, counting everything. The men of the 60th, getting impatient by the clerk’s slow count of the musket flints, repeatedly offered to help, and were repeatedly rebuffed. Historians assume that Colonel Minor and his Captains didn’t know that the British were already dangerously close to Washington, D.C. Had they known one has to believe they would have subdued the clerk (physically if necessary), grabbed what they needed, and marched off. After the men were supplied, Colonel Minor sent them to the Capitol while he remained to sign the receipts. By the time Colonel Minor caught up with his regiment at the Capitol, the 60th had received orders to march to Bladensburg, Maryland.

While the 60th Virginia Regiment was getting supplied, the American army engaged the British forces at Bladensburg. The Americans had superior numbers but their mostly untrained militia forces were quickly pushed aside by the better trained, better equipped, British regulars. American troops were in full retreat by 4 pm. The 60th Virginia, marching to the battle, soon met General Winder and his retreating troops. Winder ordered the 60th to form a line of battle on a height and cover the army’s retreat. The 60th was then ordered back to the Capitol building without ever having fired a shot.

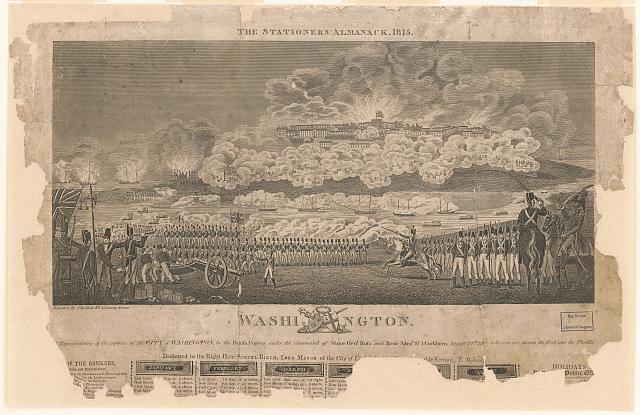

General Winder, Secretary Monroe, and Secretary Armstrong had a quick conference at the Capitol and decided to order the American forces to retreat further, abandoning Washington, D.C. to the British. The British entered the city the evening of August 24. The invaders proceeded to burn most of the public buildings, including the U.S. Treasury, the Capitol and the White House. American troops set fire to the Navy Yard themselves, in order to keep the ammunition, ships, and other equipment out of enemy hands. First Lady Dolley Madison was one of the last to flee Washington, D.C. She stayed behind at the White House and personally saw to the safe removal of Gilbert Stuart’s famous, full sized, painting of George Washington. The portrait survived the invasion and hangs in the White House today. The night of August 24th the glowing flames of our burning capital city could be seen as far west as Leesburg, Virginia and as far east as Baltimore, Maryland; they were undoubtedly visible from the Burke area. To add insult to injury, for a time the British flew the Union Jack on Capitol Hill.

The British occupation of Washington, D.C. didn’t last long. On August 25th violent thunderstorms and a tornado hit the city, putting out many of the fires. The British, tired and nervous about being so far from their ships, withdrew that same evening. Both Thomas and Francis Coffer survived the war, and returned to their homes in the Burke area. By Cindy Bennett